I. This Is My Day

“هاد هو يومي.” This is my day.

Not yesterday. Not tomorrow. Just this one.

The phrase lands almost carelessly, as if spoken by someone who has said it too many times to mean it anymore. But listen longer and you realize the repetition is the point.

This is my day. He says it again. And again. And again.

The day returns, like it always does, uninvited but inevitable.

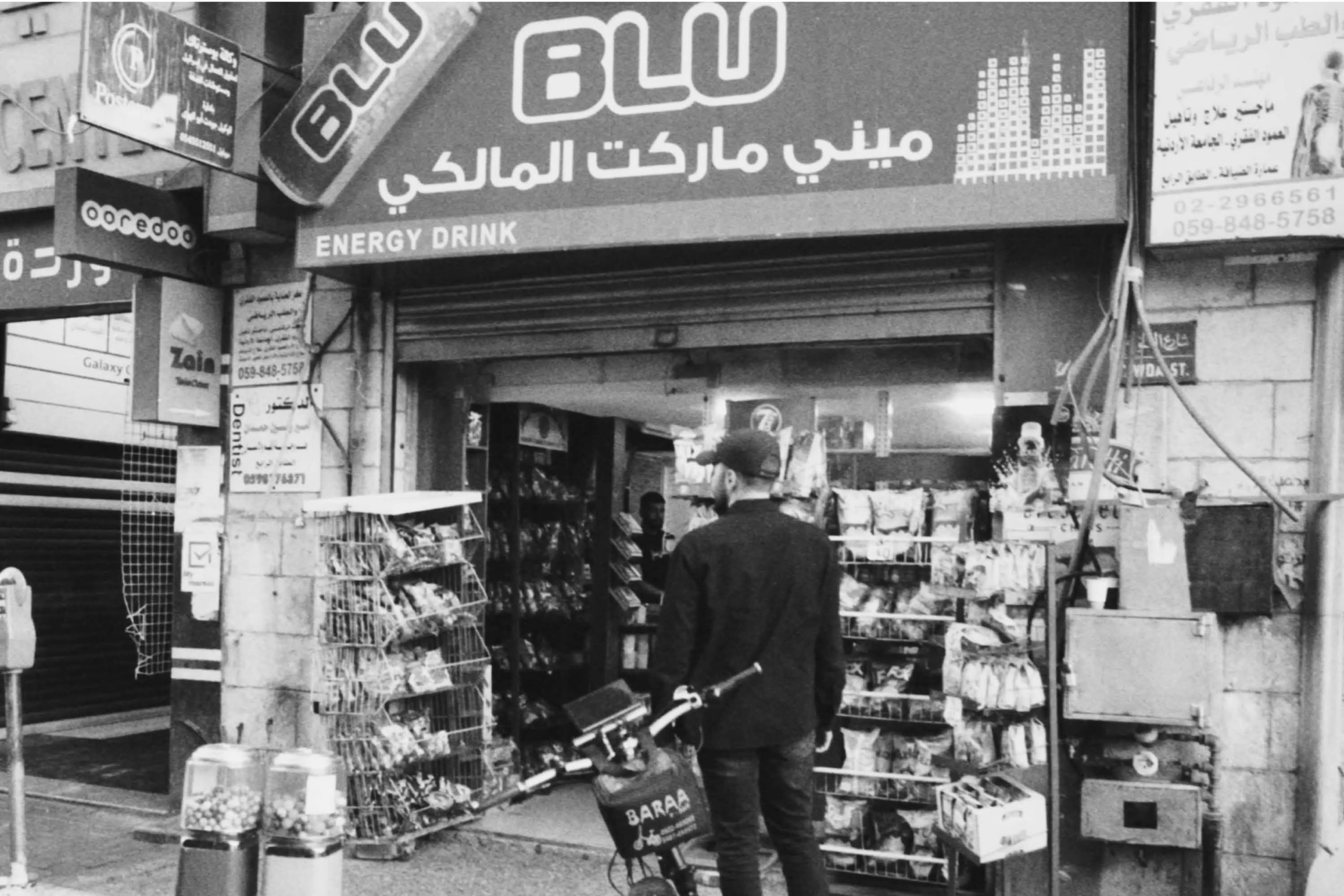

The song does not rush to announce itself. There are no fireworks, no grand entrances. Instead, it opens the way life opens in places like Ramallah or Jerusalem, quietly, reluctantly, as if the sun itself sighs. There is always this moment before the world begins where the air holds its breath, and in that stillness you hear the weight of repetition.

Because in Palestine, a new day is rarely new.

The dawn does not promise change. It promises continuity. The same checkpoints. The same faces. The same headlines. The same hope that something might shift, and the same knowledge that it probably will not. Yet still, the people rise. They brush their teeth, they make coffee, they open shop doors, they curse the morning traffic, they text their friends. Life continues, not because it is easy, but because it has to.

That is where “Youmi” begins, not with rebellion but with awakening.

“Youmi,” by Fawzi and Shabjdeed, is not a song in the way other songs are. It is not crafted for the algorithm or the club. It does not exist to entertain. It exists to record. It is a witness more than a work.

It begins like a ritual and repeats like a prayer. The loop becomes hypnotic, almost meditative. The day wakes up again and again until the listener feels caught inside its orbit. It is not a circle that imprisons; it is a circle that defines.

When Fawzi chants “قوم من نومي ولف البلاد,” meaning “Rise from my sleep and roam the land,” it feels less like instruction and more like incantation. It is the everyday command of existence itself. The words move in cycles because life here moves in cycles. The music mimics the geography: tight, confined, looping through the same streets, the same markets, the same restrictions, the same routines.

The repetition is not laziness. It is accuracy.

Because in Palestine, time itself has a different meaning. It does not stretch forward; it circles. Days are not progressions but rotations. The calendar turns but the story stays. Occupation teaches you to measure time not in years but in closures, not in seasons but in openings, not in holidays but in raids.

To say “هاد هو يومي” is to say, I woke up again in this world, and that in itself is something.

“Youmi” is deceptively simple. It is a pulse, a heartbeat, a low hum that repeats without climax. It mirrors the rhythm of a car idling in traffic or a city under curfew. There are no grand swells, only motion that feels static. It is the sound of the same road being walked twice, of the same dream interrupted at fajr.

This song breathes. It endures. It invites the listener not to look at Palestine. It asks us to inhabit its texture, the rhythm of waiting, the poetry of monotony, the quiet heroism of another morning.

The repetition is not despair. It is a way of speaking.

In Arabic, repetition is an act of emphasis, a tool of devotion. The Qur’an repeats. The call to prayer repeats. The poetry of Darwish repeats. Even the language of love in Arabic insists through iteration: بحبك، بحبك، بحبك. Fawzi and Shabjdeed inherit that linguistic rhythm, but they bring it into the digital age, into the loop of a beat. Their repetition does what Palestinian life does; it survives by circling.

The first verse we hear after the incantation of “هاد هو يومي” is Fawzi’s.

“صبحت ناسي كل شي من إمبارح (آها)”

“I woke up forgetting everything from yesterday.”

The line arrives like a sigh. There is no triumph in forgetting; there is only necessity. In Palestine, forgetting is survival. To wake up and erase the previous day is to make room for this one. The body can only carry so much weight before it must reset itself.

The word صبحت is telling. It literally means “I became morning,” not simply “I woke up.” In Arabic, the transition from night to day is a transformation of being. You do not just open your eyes; you become something else. But here, that transformation is thin, almost mechanical. Fawzi becomes morning as one changes gears in a car.

The “آها” that follows sounds casual, almost lazy, but beneath it lingers the fatigue of repetition. It is the sound of someone checking his pulse at the start of the day and finding it still beating.

Forget yesterday. Begin again. The same sky, the same street, the same fatigue.

“وقفت ألوح بالشارع (صحيح)”

“I stood waving in the street.”

The image is small and familiar, yet devastating when you think about it. He is waving for a servis, a shared taxi, the lifeline of Palestinian cities. To wave in the street is to perform a small act of hope. Every hand raised contains a question: will someone stop for me today?

The parenthetical “صحيح,” meaning “right” or “true,” is almost like a conversation with himself, as if confirming his own existence. I am here. I stood there. I did that. This small, repeated self-affirmation runs through the entire song. When the world refuses to acknowledge you, sometimes you must acknowledge yourself.

“سَرفيس نص ساعة آشرله / صف؟ لأ، من جنبي ضَل مَارق”

“A shared taxi, half an hour I waved for it. Did it stop? No, it kept passing me by.”

This is the heart of the verse, maybe of the whole song.

Half an hour, standing there, waving, a man and his outstretched arm. A single gesture stretched into thirty minutes. It is a scene anyone in Palestine knows, but it is also something larger: the condition of being unseen.

The servis is not just a vehicle. It is the metaphor of global recognition. You wave, you call, you signal, and the world passes by. You exist, but you are not picked up.

It is an image of both ordinary frustration and national allegory. The ignored commuter and the ignored people are one.

There is also something poetic about the mechanics of the servis itself. It runs fixed routes. It never deviates. Even when you wave, it cannot change its path. There is no freedom in its movement. The driver sees, but he cannot respond.

And so it passes.

“من جنبي ضَل مَارق.” He stayed passing beside me. The motion continues, but the man remains in place.

In this image, Fawzi condenses the essence of Palestinian time: everything moves around you, yet you stand still.

“هوي خال، هيني قدامك / ع الكُربة واقف قبالك”

“Hey uncle, I’m right here. I’m standing by the curb, right in front of you.”

The tone shifts from patient to pleading. He calls out, “خال,” uncle, a word of casual respect. The intimacy of Palestinian speech surfaces here. Even strangers on the street are kin. But that familiarity does not guarantee recognition. He names the driver as family, yet still, he is unseen.

“I am right here,” he says, twice. Once for the driver, and once for the world.

The repetition of “قدامك” (in front of you) echoes like a protest sign. It is both description and accusation. There is something tragic about having to assert visibility to someone already looking at you.

The curb, الكُربة, is where waiting happens. It is the border between movement and stillness, between those who go and those who remain. It is the daily checkpoint of the civilian, self-imposed but no less symbolic.

“في شرطي لابِد ع الطلعة / بستنى يخالفك ع حزامك”

“There’s a cop waiting at the slope, waiting to ticket you for your seatbelt.”

Here the scene widens. The world around the waiting man comes into focus: the policeman crouched on the hill, the looming presence of authority watching for the smallest infraction. It is an image both comic and suffocating.

Every Palestinian street has such figures. The state within the occupation, the layer of enforcement within the larger system of control. It is a reminder that even when movement happens, it is under watch.

The absurdity of the detail, a cop waiting to fine someone for a seatbelt when the entire infrastructure is crumbling, speaks to the misalignment of power. Discipline where there is no justice. Rules without freedom.

“وصلنا البلد بعدها كالعادة / اليوم بمشيش من دون فنجان سادة”

“We reached the town, as usual. I can’t go about my day without a cup of plain coffee.”

After all that waiting, the day resumes its normal rhythm. The servis arrives, the town appears, the routine continues. The line “كالعادة,” as usual, resets the loop.

The coffee that follows is ritual. In Palestine, the cup of سادة, unsweetened coffee, is not indulgence but equilibrium. It is the small daily act that holds the world together. To say “I cannot go without it” is to say, I need something stable, something mine.

There is also a quiet defiance in choosing سادة. Bitter, undiluted, real. It is the taste of honesty.

“أصلي صحيت متضايق، مش رايق / كم من نقاش اليوم بدي أتفادى؟”

“I woke up irritated, not in the mood. How many arguments will I have to avoid today?”

This is the mental weight of repetition. The body is awake, but the spirit hesitates. He anticipates conflict before it begins. Even conversation feels exhausting.

It is not only personal fatigue; it is social weariness. The country’s tension seeps into daily life. Politics in every small talk, frustration in every line at a shop, argument in every family gathering. You begin the day already bracing for noise.

The question, “كم من نقاش اليوم بدي أتفادى؟”, is heartbreaking because it is rhetorical. He already knows the answer: too many.

“ركبت الأول هَسه ع الثاني / ضايل شوي وبوصل بثواني”

“I got on the first, now on the second. A little more and I’ll be there in seconds.”

The commute continues. The voice feels almost mechanical again. The phrasing mimics driving itself, short, clipped, practical. There is movement, but no sense of arrival.

This is the illusion of progress: motion that leads nowhere.

In the geography of the occupied land, arrival is never final. Each movement is followed by another stop, another turn, another delay. “I will be there in seconds” is both promise and irony. The journey continues forever.

“بقول للحاج: “تخال فِش إشي فاتح” / قالي: اليوم إضراب يالغالي”

“I tell the old man, ‘It looks like nothing’s open.’ He says, ‘Today there’s a strike, my dear.’”

And just like that, the day pauses again. The collective decision of إضراب, strike, halts everything. The personal and the political intersect once more.

In Palestine, you never truly plan your own schedule. The country decides for you, through strikes, closures, curfews, or power cuts. Even solidarity becomes an interruption.

But there is affection in the exchange. The word “يا الغالي,” my dear, softens the frustration. It is how people here survive interruption, through tenderness, through humor, through shared fatigue.

“أنا لستُ شاعر، أنا لستُ أديب / وظيفتي أبرم وأظلني أعيد”

“I’m not a poet, I’m not a writer. My job is to talk and keep repeating.”

These are perhaps the most important lines of Fawzi’s career so far. He rejects the title of artist, claiming instead the role of observer, speaker, repeater.

The humility is not false modesty. It is philosophy. To talk, أبرم, and to repeat, أعيد, are acts of witness. He identifies himself not as creator but as echo. His art is the record of what already exists, the streets, the frustrations, the rhythms of waiting.

He refuses the romance of art. In doing so, he creates something truer than poetry.

“مسيرة فيها ١٣ واحد، ١٢ منهم أصلًا مناديب”

“A march with thirteen people, twelve of them representatives.”

A darkly comic line. The march could be a protest, but here it is emptied of purpose. Thirteen marchers, twelve of them officials, a satire of bureaucracy and hollow activism.

It is Fawzi’s way of saying that representation has lost meaning. Everyone claims to speak for the people, and no one actually walks for them. The one real person left in the march is the one who knows it is futile.

In that futility, Fawzi finds his truth. He does not represent anyone. He simply narrates.

“تفرغ عنده ديفرغ فيك / مش إنتَ الأول لأ، في قبليك”

The lines slide between Arabic and Palestinian street slang, the meaning layered. “He empties himself, then empties into you,” exhaustion passed down, energy transferred but never renewed.

“You are not the first; there were others before you.”

These words cut through any illusion of uniqueness. The struggle, the waiting, the frustration, none of it is new. Every generation inherits the same tired story.

It is cyclical again, like the beat itself. The repetition of fate.

“ولك إسمك صاير زي النار ع العلم / إنتَ قُلي وينك وأنا هَسه بجيك”

“Your name is like fire on the flag. Tell me where you are and I’ll come to you.”

The closing bars of the verse burst with sudden pride and intimacy. The name like fire on the flag evokes both fame and danger. It is a compliment but also a warning. To be known in this world is to be marked.

The final invitation, “Tell me where you are and I will come to you,” returns us to movement, to connection. Despite fatigue, despite futility, there is still communion. One man reaching another through song.

The verse ends without resolution. The day continues. Fawzi’s morning, with all its waiting and repetition, becomes a document, a testament of persistence. He has not changed the world, but he has described it faithfully. And that, in itself, is resistance.

II. Going Home Still Passes

The chorus of “Youmi” feels like a breather, a moment of lightness after Fawzi’s heavy reflections. The melody lifts, the rhythm loosens, and the words fall into the cadence of casual talk. But listen closer and the levity becomes illusion. Beneath the humor and slang, the chorus is a portrait of a system so repetitive that even fatigue has rhythm.

“والترويحة؟ برضه تِمُر”

“And going home? It passes too.”

The day’s return home, the ترويحة, should symbolize rest, closure, or relief. But here it is reduced to another motion that simply passes. It is not a destination, just another stop in the loop. That one word, برضه, also, collapses the hope of difference. Even the evening, even the small freedom of going home, becomes routine.

There is something profoundly Palestinian in that phrasing. Life is punctuated not by events, but by repetitions of events. Every commute feels identical, every ending prefigures its own restart. To go home is not to arrive; it is to prepare for tomorrow’s same road.

“مش سَرفيس؟ لا، باخد فورد / الراديو مشغل؟ حاطط أورج”

“Not a servis? No, I’m taking a Ford. The radio’s on? Playing keyboards.”

At surface level, this feels like street chatter, a man joking with his driver. But the humor carries realism. Switching from servis to Ford, the old shared taxis that shuttle between towns, marks a shift in class, a tiny flex. He is still dependent on transport, still in motion, but at least the ride is different today.

The question and answer rhythm mirrors conversation between passenger and driver, but also the rhythm of survival itself: negotiation, improvisation, small variations inside sameness.

Then the org, that cheap electronic keyboard sound so common in Palestinian taxis and wedding halls, enters the scene. It is joy within constraint. Even when the setting is bleak, the sound insists on liveliness. That tinny, nostalgic synth is the music of working-class Palestine: weddings in community centers, cars decorated for cousins’ engagements, old USBs with songs named dabke mix.

Fawzi and Shabjdeed treat it with affection, not irony. They know that this is what joy sounds like when it refuses to disappear.

“لا لا لا لا”

The chorus breaks into a sequence of “no’s.” Four, then five, then many.

On paper, it reads as filler, a hook to keep rhythm. But those لا are layered. They are the heartbeat of refusal, disguised as melody. In Palestine, the word no carries centuries of endurance. No to erasure. No to silence. No to despair. Even when sung lightly, it echoes resistance.

Each lā — each ‘no’ — lands with a kind of shrug, not shouting, not pleading, just continuing. The people here have learned that sometimes the gentlest no is the most unbreakable.

“كم من راكب؟ بس تلات / إمتى الراتب؟ فِش دُفعات”

“How many passengers? Just three. When’s the salary? No payments.”

Every bar in this verse paints a piece of economic reality. The driver counts his passengers. The passenger complains about unpaid wages. They are both stuck in the same loop of scarcity.

This is the Palestinian working day condensed into nine words: not enough riders, not enough money, but still the car moves.

The beauty of “Youmi” lies in these details. It does not romanticize poverty; it records it with accuracy and dignity. These lines could be overheard anywhere between Hebron and Nablus, snippets of street talk on the curb turned into music.

It is also a sly jab at the false promises of bureaucracy: salaries delayed, budgets frozen, development stuck in planning. The rhythm of nonpayment becomes part of the national soundscape.

“الفورد نزلنا؟ ركبنا باسات”

“The Ford dropped us off? We got into a Passat.”

And so it continues, the constant switching between cars, between places, between conditions that change but never improve. Even the vehicles symbolize economic hierarchy: servis for the masses, Ford for intercity rides, Passat for those slightly better off. The repetition of motion masks the stillness beneath it.

This is the illusion of modernity in an occupied land. Cars, roads, movement, yet all of it confined within invisible walls. You can move all day and remain in the same place.

The humor in these lines, however, is intentional. Palestinians often use humor to hold pain at bay. To laugh at life’s bureaucracy is to survive it. By reciting their day like this, Fawzi and Shabjdeed turn daily absurdity into melody.

By the time the chorus cycles through its repetitions of لا, it has transformed from conversation into trance. The listener starts to feel the rhythm of repetition the same way one feels the road’s bumps on a long ride. It is hypnotic. It is real.

The everyday becomes chant.

This is how “Youmi” communicates resistance without ever naming it. The chorus is not a cry but a groove. It carries the listener through the dullness of repetition until dullness becomes meaning.

In this world, monotony is not failure. It is survival.

III. Closed, Closed, Closed

Then something strange happens. The music does not change, but the voice does. Suddenly we hear not a rapper, not a singer, but the cold monotone of an announcer.

“بوابة الفحص مغلقة، بوابة الفوار مغلقة، دورا مغلقة، الظاهرية مغلقة…”

“Gate of Al-Fahs closed. Gate of Al-Fawwar closed. Dura closed. Adh-Dhahiriya closed.”

The shift is jarring. We move from rhythm to report, from poetry to announcement. This is the bridge, and it is perhaps the most haunting moment in Youmi.

Every Palestinian knows that voice. It greets the morning before the sun does. Broadcasts played on local radio stations each morning. They list which roads are open, which checkpoints are shut, which areas are under inspection. It is the geography of occupation turned into a weather report.

Inserting it into the song is not a gimmick. It is truth. It is the sound of the country speaking for itself.

Each closure read aloud is a small act of violence. The voice is neutral, but the meaning is not. A closed gate means a missed appointment, a delayed delivery, a canceled visit, a funeral unattended. The monotone of the announcer hides a million small heartbreaks.

The repetition of mughlaqa, closed, becomes a percussive element. The word itself starts to blend into the beat, almost rhythmic. Fawzi and Shabjdeed are showing us something profound: in Palestine, even restriction has rhythm.

The roadblocks create the country’s tempo. The barriers are not interruptions; they are the pattern itself.

When the announcer lists the towns, Salfit, Burqin, Za’atara, the listener can visualize the map tightening. The land folds into itself. Movement becomes a privilege, not a right.

The repeated instruction “يُرجى الحذر,” please be careful, is chilling. It is the polite voice of danger. A soft-spoken acknowledgment of constant threat.

“Be careful” here is not advice. It is the condition of living. The entire country exists in that sentence: aware, cautious, alert, yet always moving.

By including this bridge, Fawzi and Shabjdeed dissolve the boundary between music and environment. The checkpoint report is not background noise; it is the country’s soundtrack. It is the ambient music of every Palestinian day, the rhythm of gates, barriers, closures, detours.

The listener who does not know Arabic might hear it as atmospheric texture. The listener who knows understands that it is geography, confinement, and endurance all at once.

This moment transforms “Youmi” from song into soundscape. It is not a composition; it is a recording of existence.

“مغلق، مغلق، مغلق.”

The final triple repetition closes the loop. It is both ending and continuation. The word “closed” becomes the country’s lullaby, its daily refrain.

And yet, even as the voice declares everything sealed, the music keeps playing. The beat does not stop. The repetition continues.

That persistence, the sound moving forward when everything else stands still, is what makes “Youmi” extraordinary. It turns paralysis into pulse.

The bridge fades, but the rhythm remains. The day is not over; it simply repeats. And in that repetition, the people continue breathing.

Then Shabjdeed enters.

IV. Nothing New, This Is My State

If Fawzi was the voice of the street, Shabjdeed is the voice of the mind that walks it.

Where Fawzi documents the morning, Shabjdeed dissects the condition. His verse is less diary, more mirror. The flow bends and folds back on itself, filled with self-interrogation. The tone shifts from observation to philosophy.

“لف البلاد بعرباي ست لتر ألمانية / نمرة صفرة تعرف منها إني أنا مقدسي”

“I drove around the country in a six-liter German car. The yellow plate tells you I’m from Jerusalem.”

He begins with motion. After the checkpoint lists, it almost feels like relief, a declaration of freedom, of movement. But it is ironic. To move around the country is not liberation; it is restless circling inside limits you did not draw.

The six-liter German car is both status symbol and sarcasm. In a place where movement is restricted, power is theatrical. The luxury vehicle becomes parody, a fast machine crawling through bottlenecks.

Then he adds, “نمرة صفرا,” the yellow plate that marks Jerusalem vehicles. Those plates grant access through certain checkpoints that others cannot cross. It is a small badge of privilege within collective captivity. Shabjdeed recognizes the absurdity of that hierarchy, freedom by digits, mobility by color code.

So he starts his verse by naming both his reach and his restraint.

“لا جديد، هادا حالي / إنتَ قُلي حالك كيف؟”

“Nothing new, that’s my state. You tell me, how are you?”

This is the voice of exhaustion speaking conversationally, almost politely. The everyday greeting, kifak, becomes existential. Nothing new is not boredom; it is diagnosis. It is the static state of a place where novelty is rare and sameness is the rule.

The casual rhythm hides despair. This is how people speak when change has become myth.

“لا تريد؟ حُر بذاتك / حُر ع الاخر، حُر كتير”

“You don’t want to? You’re free in yourself. Completely free, very free.”

The irony here is sharp. He throws the word freedom around like smoke, turning it on its head. Free means nothing when every direction is blocked. The exaggerated repetition, completely free, very free, exposes the hollowness of the phrase in a colonized land.

It is the same kind of bitter humor one hears in conversation on the street: “We are free people, sure we are.” The joke softens the wound but does not hide it.

“في بلاد فيها العايب منه الحكي لا يفيد / لا يُقال، لا يُعاد، لا يُراد، لا نبيه”

“In a country where talk is shameful, words don’t help. They’re not said, not repeated, not wanted, not prophetic.”

Here Shabjdeed turns cynical. The rhythm of negation, لا يُقال، لا يُعاد، لا يُراد، لا نبيّه, is both poetry and protest. Every clause collapses language further until speech itself disappears.

It is a portrait of silence imposed by exhaustion. In such a place, truth loses its audience. People stop listening because they already know what will be said.

And yet, by writing these lines, he breaks that silence. The act of declaring that words no longer matter is itself a powerful use of words.

“لإنه هاد هو إللي بايع / بعرف كيف، بتعرف كيف؟”

“Because this one sold out. I know how it is. You know how it is.”

The tone turns personal, almost conspiratorial. The one who sold out could be a leader, a system, a person, or the abstract idea of betrayal itself. But the real weight is in that closing question: بتعرف كيف؟ You know how it is.

It is a phrase that ends countless conversations in Palestine, shorthand for shared understanding without needing explanation. It is the sigh between friends who have seen too much.

“نصنا مشاطيب ع البركة / شايفين منظرك، زفت من مصغرك / فِش أي هيبة وكل حد بكرهك”

“Half of us are written off, living by luck. They’ve seen your look; you’ve been trouble since you were small. No authority, everyone hates you.”

The verse dips into generational despair. مشاطيب, crossed out, refers to people discarded by the system, unemployed, directionless, numbed. Living ع البركة, by God’s blessing alone.

The insulted “you” could be a reflection of the collective self, the Palestinian youth seen by the world as troublemaker, criminal, or burden. The tone is mocking but intimate, as if Shabjdeed is addressing his own reflection.

It is a verse about internalized anger, the bitterness of being misunderstood both from within and without.

“لا أحد يُمثلني في المحافل الدولي”

“No one represents me in international forums.”

This line pierces through the noise. It is stark, direct, unadorned. It rejects the entire apparatus of diplomacy, the endless conferences, the token speeches. No one speaks for him.

It is a declaration of alienation from both leadership and the world. He has watched years of negotiations produce nothing but more borders. So he removes himself entirely from representation.

In three seconds, Shabjdeed sums up seventy-seven years of disillusionment.

“جماهيري قاعدة بتنطر تُقبرك / تطلب ينصرك”

“My crowd is waiting to bury you, asking God to give you victory.”

The contradiction is deliberate. The people both curse and pray for the same figure. Love and hate coexist. It is the cycle of expectation and disappointment that defines politics here. Shabjdeed exposes it with unsettling honesty: the audience does not want saviors; it wants catharsis.

“شيعي، سُني، مسيحي أو علوي / بس ينصرك أكتر”

“Shiite, Sunni, Christian or Alawi — may they support you even more.”

The verse momentarily transcends sectarianism, mocking the divisions that fragment solidarity. He lists religious identities not to separate them but to show their irrelevance to the struggle. The only real question is whether you will stand with me when it matters.

“قومٍ دونْ على أرضي تَجبّر / فتح باب رزق، قام مات، فَقِر سَكّر”

“A people who became arrogant on my land. Opened a door of livelihood, then died, went broke, shut it again.”

This is collapse written in rhyme. Every rise is followed by a fall. Every opportunity ends in closure. It mirrors the checkpoints in the bridge: open, closed, open, closed.

The fatalism here is not surrender; it is realism. Shabjdeed describes a cycle he knows too well. The system breaks even those who try to build within it.

“سيد قطب، وين الكتب؟ بودي أتفكر”

“Sayyid Qutb, where are the books? I’d like to reflect.”

A sudden shift to intellectual yearning. He invokes Qutb not to preach ideology but to signal a hunger for thought. In a society numbed by struggle, even thinking feels revolutionary. The line carries both irony and sincerity. It is the lament of a man too tired for manifestos but still searching for meaning in old texts.

“تحتاج للعون بالفطرة / بس نحن نحتاج له أكثر”

“You need help by nature, but we need it more.”

This moment humanizes the verse. After cynicism and critique, compassion appears. He acknowledges shared vulnerability, the universal need for aid, and the cruel hierarchy of suffering that decides who receives it.

“هادي سياد تورث أرض للحفاد، هذا عندك / إحنا ورطنا فقر، غم وموت ونتصبّر”

“Those lords pass land to their grandchildren, that’s your world. We inherited poverty, sorrow, and death, and we endure.”

Here he draws the ultimate contrast between classes and nations. Some inherit land and ease, others inherit endurance. It is not envy; it is statement. The verb نتصبّر, we are patient, is more than stoicism. It is theological. Patience becomes the only inheritance left.

“أمراض وراثية تخليك تضلّك تفكر / تسأل نفسك، هل؟”

“Inherited diseases make you keep thinking. You ask yourself, ‘Why?’”

The verse ends in introspection, looping back to thought itself. The disease is both biological and psychological, the inherited trauma that forces reflection, that keeps the mind awake even when it wants rest.

That final hanging “هل؟” does not seek an answer. It is the sound of consciousness that will not turn off.

Shabjdeed leaves us there, mid-question, mid-loop.

V. Begin Again Tomorrow

The chorus returns exactly as before. Nothing has changed. The same cars, the same questions, the same “لا لا لا.”

Then the refrain begins again: “هاد هو يومي، هاد هو يومي.”

The song ends where it began. The day repeats. The loop completes. The day repeats, and in that repetition, it endures.

But the repetition no longer feels empty. After Fawzi’s observation, the checkpoint announcements, and Shabjdeed’s existential spiral, the phrase “هاد هو يومي” transforms. It is no longer resignation; it is declaration.

This is my day. Still mine. Still alive.

The song closes with the same breath that began it, a circle drawn by two voices who have learned that persistence is the only victory left.

In the silence after it ends, you can almost hear the next day beginning. The same rhythm. The same road. The same heartbeat that refuses to stop.

And so it starts again:

“قوم من نومي ولف البلاد”

Qum min nomi w-liff el bilad

Rise from my sleep and roam the land.