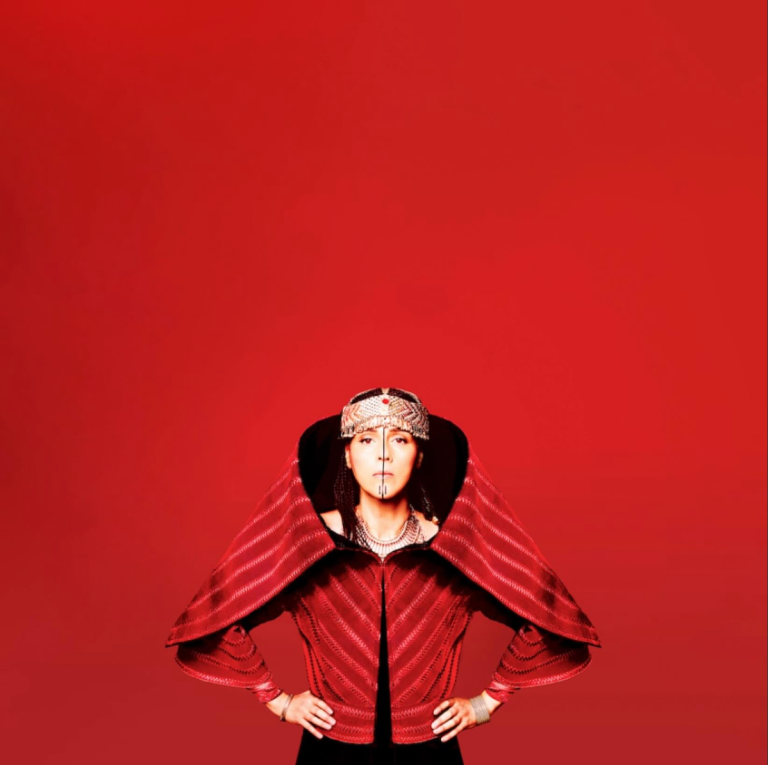

Thirty minutes into my conversation with Alsarah at a Brooklyn café in early July, the weather shifts; what started as a clear summer evening becomes a storm, with rain falling heavily on the awning above us. Unfazed, the 43-year-old Sudanese-American singer sits back, her curls wrapped in a floral scarf and gold jewelry catching what’s left of the light. There’s a steadiness about her that makes the chaos feel almost incidental.

Earlier this year, the band she fronts, Alsarah and the Nubatones, released its third studio album, Seasons of the Road; I joke that the temperamental weather seems hellbent on making this point. The East African retro-pop record has already reached audiences around the world, and when we met, the group was gearing up for a late-summer and early-fall tour with multiple stops across the US East Coast, as well as Tunisia, Cairo and Jordan.

The new work feels distinctly ancestral: it is both sultry and measured, and like other Nubatones releases it comes across as political, where the rhythm itself becomes revolutionary. That framing makes sense, considering the devastation in Sudan, which Alsarah says shaped her approach while also forcing her to reckon more publicly with her own history of exile.

“I am a political entity. The reason I am here is because of politics,” she tells me. “If you consume me and you want to be here for this, you have to swallow that.”

Claiming a Genre

Alsarah didn’t land on the label “East African retro-pop” by accident. For years, she resisted the term World Music, the catchall that pigeonholes non-Western artists. Nor was she interested in being filed under Traditional. “I saw no reason why I needed to adhere to a rule that really was not a rule,” she says.

Some of that resistance stems from the many labels that have been thrust upon her. Her family’s journey as refugees — from Sudan to Yemen in 1989, then to a village in western Massachusetts in the 1990s — meant others were constantly defining her.

In Sudan, she was taught that she was Arab, only to discover later she was not seen or treated as such. In the US, she was categorized as a refugee, as if it were an ethnicity. On top of that, hers was one of three Black families at school, where she says she experienced “complete isolation.” At the same time, her mother and father held firmly onto education as a path forward. In 2004, all three graduated together — her parents with PhDs and Alsarah with a BA from Wesleyan, where she wrote her thesis on Sudanese zar music.

That year, Alsarah moved to New York, where she performed freelance gigs. Her turning point came when she joined the Zanzibari band The Sounds of Taarab and began exploring taarab, a genre rooted in Swahili coastal culture, blending East African, Arab, and Indian musical traditions.

Her examination of taarab opened a door to East Africa’s history and its often-overlooked ties to the Arab world. These cross-cultural links in turn led her back to the music of her motherland, anchoring her artistry in a Sudanese lineage she had been circling for years.

“Sudan’s sound and history were a part of this shared collective history,” she says. “And the conversation between the Arab world and East Africa is not a conversation that’s really familiar, even to Arabs.”

Around the time she formed the Nubatones in 2010, East African voices had little visibility, especially those singing in Arabic or bilingually. That realization helped frame how she defined herself professionally, in a landscape where the notion of African sound often defaulted to West Africa or South Africa.

“I wanted East Africa to really be a prominent section of the conversation we were having,” she says. “I knew I wanted to do something that bridged pop and retro, but not traditional, necessarily. I also wanted people to understand where I came from because when I started, nobody else was doing this.”

“I like to explore myself by thinking of myself as a nation (…) an unexplored nation.”

In those early New York years, Alsarah sang at Brooklyn bars, never imagining her music would travel beyond them. But the lack of representation pushed her to create for herself. ”I started making music because I couldn’t find me in any of the stories being told around me,” she says. “From the beginning, my target audience was me.”

What began as a personal inquiry would unfold into a trilogy of albums for the band — Silt (2014), Manara (2016), and Seasons of the Road nearly a decade later — each tracing a different facet of displacement and identity.

Third Culture

Even Alsarah’s name tells a story of reclamation. She was born Sarah Mohamed Abunama-Elgadi, but her mother had wanted to call her Albushra Assara, an old Arabic phrase meaning “a blessing of joy.” Her relatives discouraged the choice, dismissing it as the equivalent of naming someone “Agnes.” Years later, Alsarah chose it as her stage name.

Alsarah was just four when she had her first musical memory. While the family was still living in Sudan, a bootleg cassette produced by a leftist Sudanese writers’ collective played at home. The Communist Party–sponsored tape contained pro-voting and anti-imperialist songs that circulated underground in secret. She took in every word, she says, in what would prove to be an inkling of her rebellious nature.

After the 1989 coup, the family fled to Yemen. In 1994, they were forced to flee again, this time by Yemen’s civil war. Upon moving to the US, where they sought asylum, people often asked Alsarah what Sudan sounded like; she realized she didn’t have an answer. “People were like, where the hell is Sudan even?” she says. “So it started me on this hunt for what it sounds like from [another] place. I started the search indiscriminately.”

As a teenager in the US, Alsarah also immersed herself in Americana, including early blues, road worker songs, Appalachian and Gullah traditions, and shape-note singing. Having arrived in the US at 12 with next to no English, she spent hours in solitude, with libraries and used record stores acting as her “free babysitters,” as she put it.

Alsarah speaks with a quick cadence, her words tumbling out in bursts of conviction, then slowing into pauses, as if she’s measuring the weight of what she has just said. There’s warmth in her laugh, but also a flicker of impatience, the sense of someone who has more to say than time will allow.

After taking one such pause, she explains how discovering Zanzibari music shifted her understanding of identity and belonging. The shift began with difficult realizations about her own community and questioning the narrative that Sudan was seamlessly part of the Arab world. The illusion unraveled once she left home and was not welcomed as an equal elsewhere in the region.

“We think of healing as magical and lovely (…) No, it’s a fucking shit show of falling apart, thinking you’re fine, falling apart again, getting up.”

The history of taarab itself reflected these colonial entanglements. Introduced to Zanzibar during Omani rule in the late 19th century, taarab evolved as the island became a British protectorate in 1890, a period when it was deeply enmeshed in both the Indian Ocean slave trade and the clove plantation economy. As Alsarah learned this context against the backdrop of her experiences with anti-Blackness and rejection, Zanzibari music became a revelation: it showed her how sound could serve not only as a record of colonization and brutality but also as a bridge, carrying memory forward without being reduced to suffering.

“To read about [taarab] from another place that had no personal trauma [attached] to me allowed me to really open my eyes in a way to sound and to music,” she says. “I started to look at it almost as a history carrier, not as a trauma holder, but as a bridge holder.”

This reframing was her entryway into understanding how collective wounds can be transformed into cultural expression, a process she likens to the Nubian “Songs of Return,” where “a huge moment of trauma was absorbed into the culture and turned into this golden field of giving,” she says. “It releases you of the narcissism of thinking that your pain is the first or the most special.”

Now, as she watches Sudan’s current crisis unfold from afar, this way of seeing has taken on a deeper meaning. The war is not a rupture that began recently, she says, but a continuation of divisions that touched her childhood and forced her family into exile. She has long responded musically to such instabilities, though not necessarily in ways that fit expectations of urgency or nationalism. Rather, she channels her people’s pain into a body of work that threads past and present, guided by what she calls “the strength of softness” — the courage to remain vulnerable.

The war has understandably been devastating for Alsarah to witness, but it has also sharpened her focus and deepened her resolve to help others navigate the diaspora without losing themselves.

She argues that nostalgia can become a trap akin to addiction, keeping exiles and émigrés suspended between a homeland that has fundamentally changed and a reality they refuse to inhabit. Her own ensnarement with nostalgia lasted nearly two decades before she broke free, and that experience now informs her belief that people can resist its allure, not by forgetting the past, but by letting it shape the future.

The Future Normal

Alsarah was among the first wave of Sudanese to leave in the 1990s, eventually arriving in the US as a refugee and living undocumented before securing legal status. She often bristled at the way the West reduced “refugee” to an identity instead of recognizing the designation as the outcome of policy and war. But as millions more Sudanese have been displaced, she has begun to reclaim the term, acknowledging both its permanence and its potential. Becoming a refugee changes you irrevocably, she says, “but it’s really just a gateway to the next phase of you.”

Amid Sudan’s mass exodus, Alsarah insists refugees are central to the future. “We are the future normal,” she says, pointing to the wars and climate shocks set to uproot countless others.

“We’ve tried smashing identities into one sauce called national identity – that doesn’t work. It makes people feel erased. I’m excited about this indigenous-oriented global culture.”

In her view, what is happening to her fellow Sudanese today is not an exception, but a preview. Her music, which has consistently been influenced by exile and return, seeks to ensure the voices of the displaced are heard as the authors of what comes next, rather than as afterthoughts. “The next movement is so deeply indigenous and post-borders, and in celebration of the micro,” she explains. “And that micro is what is going to allow us to actually reach a place of heterogeneous unification.”

This vision extends to how she believes communities might organize beyond traditional boundaries. Alsarah recalls how Palestinians stood by her side, their solidarity rooted in a common language of displacement and erasure, rather than the concept of Arabness. That empathy opened up space for conversations driven by truth and justice, not nationalism.

“We’ve tried smashing identities into one sauce called national identity,” she says. “That doesn’t work. It makes people feel erased. I’m excited about this indigenous-oriented global culture.”

The question of home has remained fluid for Alsarah. In New York, she moved between apartments in the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Crown Heights and Ditmas Park, navigating gentrification by relying on the informal networks of immigrant life.

She faced slumlord harassment and eviction attempts with stubborn defiance. At one point, she broke into an empty apartment to access a working refrigerator, telling her landlord, “I’ve survived two wars. You are not the person between me and a fridge.”

Through it all, Alsarah cultivated her artistry. New York, she says, lets her make music without sacrificing any part of herself. It embraces multiple identities and will welcome you, as long as you commit to community and follow the city’s unspoken rules: mind your business, don’t talk too much, and refrain from snitching. “I will never leave this city, this is my homegirl,” she reflects. “We are ride or die together.”

Her daily routine follows its own rhythm. She protects the early morning hours, between 4 a.m. and 7 a.m., when her ideas flow freely. “That’s when I’m the smartest,” she says half-seriously. She’s also fiercely devoted to her plants — most of which she has rescued from the streets — calling herself a “ferocious plant mama.”

Alsarah began crafting Seasons of the Road in 2019, in the wake of Sudan’s unrealized revolution, a moment that left her unmoored. The first track she wrote, “Men ana” (“Who am I”), captured that disorientation, the feeling that both her country and her career had betrayed the futures she had imagined for them. Its opening was so overwhelming that she sobbed while writing it.

Her disillusionment broadened to the industry itself. She had entered it with hopes of remaining independent, but what she encountered felt like a modern-day “plantation model”: record deals promised success at the expense of her autonomy, demanding she compromise her voice for recognition.

“(Nubian music) releases you of the narcissism of thinking that your pain is the first or the most special.”

From 2016 to 2019, Alsarah toured nearly eight months of the year and released three projects in quick succession, which she says were “pushed out of me like boom, boom, boom.” The grind depleted her and made her question her sense of self.

“Men ana was a song of questioning. I suddenly didn’t know who I was anymore,” she recalls. “Everything I’d hoped for, everything I’d been waiting for, everything I dreamt of came crumbling down.”

The timing compounded her despair. As Sudan’s revolution faltered, she also had to contend with the end of a long-term relationship. Touring itself became a form of trauma: marketed as a “voice of diversity,” she experienced constant harassment at airports and interrogations as she was expected to play the part of the resilient, “happy refugee.” “My heart just broke in every single way,” she says.

Still, that period was formative. Witnessing the refugee crisis while being subjected to suspicion taught her hard realities about the industry and fame. Many artists perceived as thriving, she realized, were just as trapped or compromised.

Despite her exhaustion, Alsarah never ceded creative control. What she lost wasn’t agency but naivety — faith in gatekeepers and institutions. The wake-up call was sobering and liberating: “It made me realize everyone is the same, everyone is good and bad,” she asserts. Those lessons seeped into the long gestation of Seasons of the Road, which she worked on sporadically until the pandemic forced her to slow down.

Beyond being just an album, what later emerged was a blueprint for sustainable artistry.

Seasons of Healing

Guided by older mentors, Alsarah redirected her energies toward longevity. She admires artists who continue creating into their seventies and eighties, whose music has endured beyond the industry’s churn. Figures like Toshi Reagon, Bernice Johnson Reagon, June Millington, and the late Zanzibar icon Bi Kidude model the sort of musician she hopes to be — not merely performers, but cultural guardians, valued as much for the communities they have nurtured as for their art.

Building that kind of sustainable practice has meant confronting uncomfortable truths. Seasons of the Road became her meditation on that process, and her path to recovery. Its creation mirrored the disarray of the journey, marked by breakdowns and false starts. As an immigrant, refugee, and Black woman, nothing has ever been guaranteed; the album couldn’t be rushed, and finishing it required her to finally stop and listen to herself.

That process of falling and getting back up — Sudan’s coping mechanism, as she calls it — is what makes her feel most connected to her heritage. “We think of healing as magical and lovely,” she says. “No, it’s a fucking shit show of falling apart, thinking you’re fine, falling apart again, getting up.”

During the reckoning and healing, she allowed herself to write without industry expectations dictating her moves. One song on Seasons of the Road, “Bye Bye,” is her debut official English-language track. Early in her career, she had written unreleased songs in English, but deliberately chose to prioritize her Sudanese identity. She was determined that her family and community would recognize themselves in her work.

“I was like, I want people to know who my family is. I want my aunts to listen to this. I want them to feel included. I don’t want people to think of me as another American artist who’s trying to explore her roots,” she says. “I am a Sudanese artist… and I wanted to show that first.”

The decision wasn’t about rejecting English or American influences, but about establishing her foundation before exploring further. Now, having spent years channeling energy into that foundation, she feels more comfortable turning to English.

Sustainable artistry means integrating different components of herself into work that can endure, Alsarah tells me. “My life’s work is around tying all the other mes together. New York is the closest I’ve ever come to pulling all those pieces together,” she says. “But it’s hard. There’s different mes, and they exist in different rooms. It’s like I’m trying to put together a bag, and I keep forgetting things in the other room.”

Building Community

Alsarah is well on her way to becoming the cultural guardian she envisions herself to be. She is in the process of codifying Sudanese sounds, hoping to build a non-colonized musical vocabulary. She sees this effort as addressing a critical gap: the lack of a framework for naming rhythms outside Western notation or Arab maqams. “We need our own system,” she says.

“I started making music because I couldn’t find me in any of the stories being told around me.”

That commitment to building sustainable, independent systems extends to her aesthetic. She draws inspiration from her 97-year-old grandmother, Zainab, a seamstress who ran an underground clothing factory in Sudan, and occasionally designs outfits for her. With sustainability in mind, Alsarah loves to thrift and wear handmade pieces, learning to “dress like a spaceship for $3.75.” At a performance at the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Art (MoCADA) in Brooklyn in June, she wore a skirt remade from curtains; today, she is in a crisp white tank and denim cutoffs. As such, the singer resists both the expectation to “dress African” and the pull of Western assimilation. “I’m doing what I’m doing,” she says. “You can come for the ride.”

Just as Alsarah pushes back against being boxed in aesthetically, she has sought to assemble a band that embodies her vision of community. Her sister, Nahid — the “queen of harmonies” — learned keyboards on the fly and began writing full lines for Manara and Seasons of the Road. Around the siblings, the Nubatones have formed a steady ensemble: Rami El Aasser on percussion, Brandon Terzic on oud and ngoni, and Mawuena Kodjovi on bass. Forming a band with Nahid and her friends was a means to forge a family business, an immigrant dream of keeping loved ones close while working together.

Alsarah’s creative method reflects her ethnomusicology training: she composes first, then analyzes. Each song begins with a spark, such as a bass line, a looping sentence, or a melody with no words. “I like to explore myself by thinking of myself as a nation. I am a nation, an unexplored nation,” she says.

Once released, songs no longer belong to her; what matters is that others see their own journeys mirrored in the music. That same approach guides her live shows, which she calls “acts of radical socializing,” where people can gather and bring their whole selves.

Her practice now spans various cultural and humanitarian projects, including producing collaborative works with Sudanese visual artist Ahmed Umar, which have been showcased at the Venice Biennale; coordinating emergency funding initiatives for grassroots organizations in Sudan via her non-profit, Sunduq al-Sudan; and facilitating musical residencies for displaced Sudanese musicians in Uganda. “I want to be able to facilitate spaces that allow for safe growth,” she says.

She’s also regularly chasing sounds across continents, from Inuit breath singing to Korean singer Lee Hee-moon, whose music she is “obsessed” with. This summer, she performed a duet at Georgetown University in Qatar as part of a series about Sudan. “I truly missed the energy of the crowds [in the Middle East],” she said of her trip to the region. “It’s a different level of getting it.”

In the end, each project becomes another way to build the post-borders, indigenous-oriented culture Alsarah hopes for, one that centers the exiled not as victims but as visionaries. “The majority of the world is about to be me, you, and us,” she says. “Around the corner, honey.”

Incidentally, “Men Ana” opens with the sound of rain. In its lyrics, Alsarah sings of a dead end, a moment of stillness before the sandstorms. And then she asks: who am I? If not for the love, the longing, the relentless journey. Ultimately, Alsarah doesn’t answer. She lets the question hang.

By the time we finish talking, the real storm outside has passed. Alsarah gathers her things and disappears down the block, steady in motion, as ever. As the skies clear, Brooklyn awaits — and so does the work.

Arab Films Are Reaching The Oscars, But The Industry Is Still Lagging

Four Arab films make the Oscars shortlist this year, marking a historic moment for an Arab cinema still struggling for sovereignty.