It was no surprise to me that DJ Snake was incredibly difficult to get a hold of. Between a packed festival summer and a world tour continuing well into 2026, his new album title, Nomad, describes his perpetually itinerant state just as much as his global music style.

An interview was planned and postponed, derailed by this new super-flu jetting across the world, sparing not even the rich and famous, which has now also caught up to me in Tangiers. Mid-tour, we chased him from Dubai to Doha to Riyadh, finally catching him backstage at Soundstorm Festival and squeezing in a quick chat between a press conference and his first hip-hop set in years. The lovely Salma Ali graciously stood in for me in conversation with DJ Snake, lending her journalistic expertise to the interview we had chased across the region.

Salma described his cabin in the artist village as small, but comfortable. They sat opposite one another – him on a big red sofa, with one arm draped across the back. She sat on a chair, and a couple of lamps lit the room from the corners. She described him as confident, open, effortlessly cool, but it was in here that DJ Snake admitted to a fear that continues to claw at him before shows, even at the peak of his career.

As a young French DJ from Ermont, a Parisian banlieue that inspired the multicultural DNA of his music, William Sami Étienne Grigahcine started out playing in hip-hop clubs, and occasionally tagging walls. His graffiti career was shorter than his musical one, but from it came his stage name – Le Serpent, or The Snake – a title bestowed upon him in recognition of the cunning way that he eluded the police.

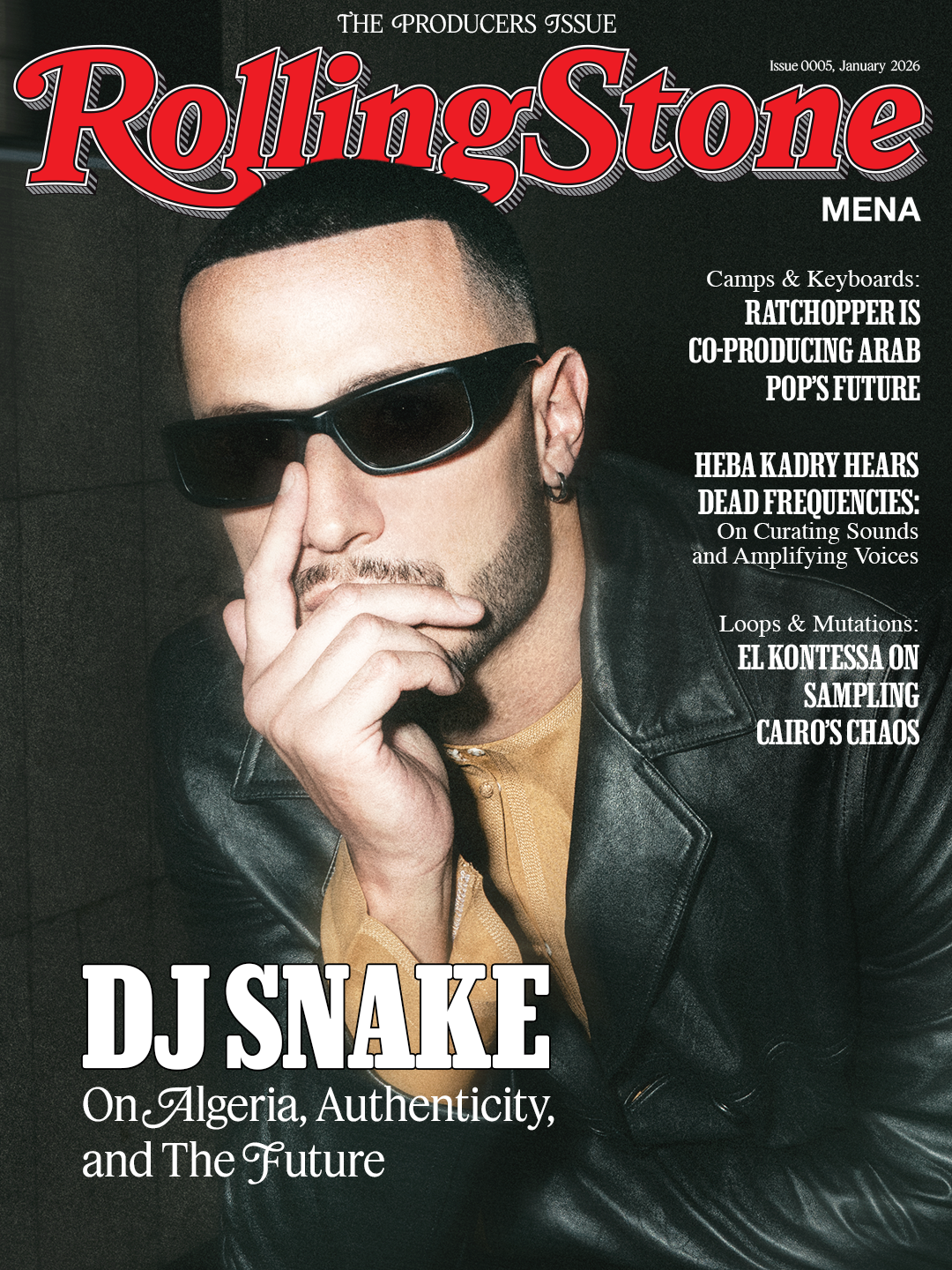

When he started playing at festivals, well over a decade ago now, he was struck by the sea of people just staring at him. “In the clubs, people were dancing, but now they were just looking at me, like I was gonna do some magic tricks or some shit, so I was panicking for real. I was petrified of making a mistake, and one of my friends told me to wear some sunglasses so that I couldn’t see the whole crowd. Now it helps me stay in the zone, stay focussed.”

That is how DJ Snake’s signature shadowed look came about, and the sunglasses stayed on even for the interview. But although the shades helped to remedy his initial stage fright, the pressure of artistry, of performance, of entertainment, never subsides.

“My job is to be a performer. So you have to perform. You have to be the best, every time. It’s like being a footballer – each game, he has to score a goal. It doesn’t matter what he did last season, or two seasons ago.” He is frank about the demands of international stardom, dispelling the illusions of grandeur we are so accustomed to seeing on social media and onstage.

At Soundstorm, he passed on his hits – the ones that everyone knows, like “Turn Down For What,” “Lean On” and “Loco Contigo” – in favour of a return to his roots. “Tonight, it’s DJ Snake from 2006. Just me, my skills and the crowd.” He took a breath. “I’m nervous.”

When the topic was fear, or the future, he oscillated between French and English. We asked him about his musical reservations going forward, and if his international acclaim had done anything to combat the imposter syndrome that plagues every star in their field. Here, William drew a distinction between nerves and a lack of self-belief. Pressure is a constant, sure, but he doesn’t believe himself to be an imposter. Confidence got him this far, after all.

“I prayed my whole life to get to this position. Comment dit-on ‘mon héritage’?” He turned to his manager, who offered “Your heritage?” “Non, non, non. Fuck! Oh, my legacy!” and he continues: “I can’t lose my legacy. What I’ve done, I did it. I earned it. It’s mine. When I go anywhere in the world and I play those classic DJ Snake songs, everybody knows them, and everybody sings them – that’s forever. I’m not scared of losing that, but I keep moving.” This is where the challenge lies for William, in his tendency towards novelty.

DJ Snake is secure in his discography, but disinclined to musical stagnation, and with every new venture come new obstacles. His global style is his signature, but refusing to stick to one brand, one format, or even one cultural genre, means that although his confidence never falters, comfort and self-assurance must be sacrificed at the altar of progress.

It’s been six years since the release of Carte Blanche, DJ Snake’s last studio album, in 2019. “I thought I was done with the album format. I thought maybe I’d still do EPs, but I was tired and bored of the formula. I thought maybe I’d just do singles for the rest of my career.” Alas, Covid locked us all away, and while I was learning TikTok dances for videos that remain in the drafts to this day, William was producing… nonsense.

“You’re either gonna make some dope shit, or some bullshit. No matter what you use – AI, whatever – it’s all about the ideas.”

Nomad is an album which makes little sense thematically, unless the theme itself is disparity. “I made loads of songs during lockdown that I wouldn’t drop on their own. The concept of Nomad was just a great excuse to say fuck it. Fuck cohesion.” William likes to think of the album as a passport, where each song is a passport stamp. In seventeen tracks, Colombia, Zimbabwe, South Korea, Senegal, Jamaica, Egypt, Mexico, France, the UK and the US are all represented through cultural sounds and artistic collaboration.

On past tracks, William has collaborated with artists before they’ve hit their peak, like Swedish singer MØ on “Lean On.” Other tracks, however, feature already globally-known figures, and there appears to be little to nothing threading all of his picks together – not acclaim, not location, not style. I wanted to know more about his criteria for collaboration, and how he finds his people. “There are no rules,” he said, all very laissez-faire. “Sometimes I’m sitting at dinner, and I hear something I like in the restaurant, and then I Shazam it. Then, I reach out to their management, or directly on Instagram.”

I enjoy the idea that DJ Snake is using Shazam just as often as me, or perhaps even more. I wonder if he turns down the brightness on his phone and discreetly angles the screen away from sight, the way the rest of us do when we’re embarrassed that we’re not already familiar with the tune.

“Other times, I bump into people in the green room at events, and we vibe, we exchange numbers. Boom, boom – it’s like that. I keep it organic.” Perhaps because it’s so organic, and William has forged his own special connections within the industry, there are some sounds we hear from him more than others. A Latinx, reggaeton beat, for example, is something I grew up associating with DJ Snake, long before I learned that he, like me, is half-Algerian.

We asked him if he was conscious of working with one cultural sound too often, of inadvertently making it his brand – without mentioning any Latinx association – but, respectably self-aware, William didn’t answer with a yes or a no. Instead, he laughed and said sheepishly: “For this album, I wasn’t gonna do anything in Spanish. But I made a beat, and J Balvin heard it. Last-minute, he decided to jump on it. And I was not trying to make reggaeton, but you know…if the song is fire…” He grinned cheekily and shrugged his shoulders with that.

And to his credit, the song – titled “Noventa” – is fire. It feels to me like a refreshed version of his last collaboration with J Balvin, edgier and more energetic, to mirror William’s own musical direction with his new persona, The Outlaw. We asked him more about his Hyde later on.

“I am trying to keep a balance though. I can’t do three or four releases of pop music back-to-back, because that’s not who I am. I get bored really quickly.”

At this, Salma jumped in: “You need a challenge.”

“Yeah, definitely. I need to keep challenging myself, and I need to surprise people. If you expect me to go left, I want to go right.”

It seems that although the natural habitat of the snake is stagnant water, DJ Snake prefers to create ripples. However restless he may be though, musically and geographically, one region has remained ubiquitously absent from his work: the MENA. Despite his Algerian heritage, his only musical acknowledgment of the region to date is contained in just three tracks, out of over one hundred: “Disco Maghreb,” “Trigue Lycee” – Remix with Cheb Khaled, and most recently, “Cairo Express” with Islam Chipsy.

We posed the question: “Are you following the MENA music scene at the moment?” And he replies, with enthusiasm: “Of course!” Salma was surprised, and honestly, so was I, because there isn’t much evidence. Why doesn’t he feature more Arab music, paying homage to our culture just as much as the rest of the world? His answer to this surprised me again.

“For my live shows, I do remixes, but it’s very tricky to touch Arabic music because it’s so beautiful. Some classics are too beautiful to touch and I respect them too much. I’d rather create something new, something original, and let those legends stay perfect. Sometimes the bravest move is knowing when not to change anything.”

It took William years to attempt an Algerian-style track, because he was so afraid of getting it wrong, offending the community or ostracising himself – a preoccupation that we diaspora kids are all familiar with. Though “Disco Maghreb” was quickly integrated into the celebratory canon of North Africa, he remains wary of ruining a good thing, or inadvertently cheapening its impact by trying to recreate it.

“Disco Maghreb” was my chosen graduation song. I took a photo of my Algerian father with my framed degree on the day and plastered it all over my Instagram to the sound of “Aywa, aywa, jib wahda, jib wahda…” It was a big day for me, but a bigger one for my father – the culmination of sacrifices that I cannot count, and over fifty years away from his country. I thought it was a fittingly celebratory tune to accompany the photo of him, suited and booted, grinning stupidly on the dehydrated lawn of Senate House, because I did, in fact, “jib wahda.”

So, although I wish DJ Snake would give us another, because “Disco Maghreb” is a tender track for me, I appreciate his caution. Perhaps his reticence is something to be admired, in an era where the arbitrary habibification of electronic music is slowly but surely becoming an insulting co-option of our culture, where at first it was an appreciative nod to the region’s musical contributions.

“I can’t do three or four releases of pop music back-to-back, because that’s not who I am. I get bored really quickly.”

Habibification, as Mai El Mokadem puts it, refers to the “flattening of Arab sonic identity into an aesthetic,” but DJ Snake sidesteps this trap of selective borrowing because his music is driven by pure love for the sound, by childish excitement rather than strategy. Instead of flattening them, he puts Egypt and Algeria into relief with “Cairo Express” and “Disco Maghreb.” In the former, he underscores the modern reality of Egyptian sound, demonstrating an appreciation of Mahraganat, which hasn’t been shown half the love that old Egyptian classics have in non-Arab spaces.

He describes how he landed on an Egyptian track for Nomad: “I was in Cairo, and I was walking down the street, and I heard a taxi playing really loud music. I was like: What the fuck is that? And I tried to Shazam it, but it didn’t work! So I chased it down the street and I asked the driver what the song was, and he showed me a YouTube page. I took a picture, but it was all in Arabic, and I can’t read Arabic. So I had to do some research on the style, the genre of that music, and then I learned about Mahraganat from an Egyptian friend, who put me in contact with Islam Chipsy.”

He laughs as he continues with his story, and I can actually hear him beaming from ear to ear. “I was like ‘Islam! Let’s work together! But Islam is crazy. When I was trying to give him feature credit, he was like ‘No! I want cash.’ And I was like ‘Bro, it doesn’t work like that.’ And he just kept saying ‘No, no, no! Habibi, I want cash.’ I was so confused, but that’s why Islam doesn’t have a feature.”

Although Chipsy’s name isn’t on the track, “Cairo Express” was produced in collaboration with an Egyptian artist, which I think is why it really does sound like Egypt, in the same way that “Disco Maghreb” captures the essence of Algeria. In 2003, Jay Z sampled Abdel Halim Hafez’s “Khosara Khosara” for his track “Big Pimpin” – without crediting the original – and Led Zeppelin played with the Egyptian Orchestra in 1994, just as Khaled, Rachid Taha and Faudel did in 1998 for the opening of 1,2,3 Soleils. Many have sampled the sounds of Egyptian antiquity, and Egypt’s golden twentieth century, but “Cairo Express” mirrors what the streets of the city sound like today.

Mahraganat, the genre that inspired the track, constitutes a huge amount of what ordinary Egyptians dance to, and what a contemporary Egyptian celebration sounds like. DJ Snake features fast-paced drum beats, shaabi maqsoom rhythms and distorted reed sounds made with a synthesiser, often found in the songs of other Mahraganat kings, like Hamo Bika, Eslam Kabonga and Essam Sasa. Foregoing the fantastical, breathy minor scales of snake-charmers found in appropriative electronic music, DJ Snake does justice to the name of the track.

I intended to push him on his relationship with Algeria, but upon the first question that Salma asks him on my behalf, he gives an unexpected answer which in many ways answers all of my questions at once – even the ones that she didn’t have time to pose to him.

I asked him to describe his relationship with Algeria – “Very strong,” he said – and then he told us about his mother, and his childhood. “Just like I am super proud to be French, I am so proud to be Algerian. My mum is Algerian, and I grew up with her music, her food, her culture – everything. So…I can’t choose.”

His closing comment is interesting to me, because Salma didn’t imply any sort of comparison with France, but it is a conversation that the French-Algerian diaspora is accustomed to having time and time again. Even as a Moroccan-Algerian who grew up in the UK, I am familiar with the trope, and here in Tangiers, I am asked to pick a side between Morocco and Algeria every day, with every development, every football match, and every UN resolution. DJ Snake, too, it seems, internalised a similar polarity a long time ago, and has probably become weary of journalists and fans asking whether he sees himself as French or Algerian first.

Salma jumped in with what I was thinking.

“You don’t have to”, to which William says: “Yeah, 100%,” but he doesn’t sound very convinced.

A couple of weeks prior, I had written up the interview questions for DJ Snake with the intention of getting a very Algeria-centric conversation out of him. However, upon reflection, and upon listening to his fatigue when faced with questions about his Algerian-ness and his connection to the MENA, I have found a real appreciation for the way that he has decentralised his identity as a diaspora kid in his work.

Actually, I think it would be remiss to write about him with only our Algerian connection in mind, not only because most are unaware of his heritage, but also because he produced the soundtrack to my non-Algerian experiences, and my adolescence in the UK. I used “Disco Maghreb” to pay homage to my Moroccan-Algerian roots at graduation, but “Lean On,” “You Know You Like It” and “Taki Taki” were all tracks that played at house parties when I was a teenager, as a backing track to dozens of firsts and hundreds of seconds. Somehow then, DJ Snake’s discography, in all its itinerancy, represents multiple stages of my life, and maybe yours too.

I asked my brother what he thought of DJ Snake, and he was confused until I typed out “Disco Maghreb”. At this, he recognised the name, before becoming increasingly confused when I followed that with “Loco Contigo.” He, like many, had never made the connection between one version of DJ Snake and the other.

What is more, when I was digging around for a sense of DJ Snake’s public perception, I got a lot of the same from friends: confusion, followed by nostalgic excitement. And here’s a little known fact: one of William’s first big jobs was producing the track for Lady Gaga’s “Government Hooker” and “Do What You Want” on her 2013 album ARTPOP, so no matter what kind of teenager you were, you probably have some nostalgic tie to a song on DJ Snake’s repertoire.

At this point in the interview, a thumping bass begins in the near distance, making the phone vibrate. Someone is mic checking before the show, and we are running out of time.

“Are there any MENA artists you’d like to collaborate with?” Salma asks.

In his elusive, serpentine style, he doesn’t offer any specifics, but he says “I really like what’s going on in Iraq. They have some crazy shit. I don’t even know the names, but I have them all on my Spotify.” Perhaps we’ll see a choubi-style song from DJ Snake next, to add to his slow-growing MENA discography.

2020, the year that William began to put together the bulk of what would eventually become Nomad, was the Chinese Year of the Rat. It was supposedly a year of flexibility, despite our limited capacity for movement. 2025, however, is the Chinese Year of the Snake, symbolising a time for strategic growth, personal transformation, and the shedding of old skins. Fittingly, DJ Snake shed his skin late last year, introducing his new venture as The Outlaw.

The Outlaw performs with a new, much more experimental sound, which William describes as “fully embracing the heavy, bass-driven side of who I am as an artist.” In a way, The Outlaw is DJ Snake pushing his nomadism and his distaste for codified formats to the nth degree. “It was born from a desire to break away from mainstream expectations and reconnect with something more raw and instinctive. I didn’t want rules; just pure energy.”

William debuted as The Outlaw at Lost Lands in Ohio and closed 808 Festival in Bangkok this year, showcasing a much more aggressive and intense style. “It feels more honest,” he says. “And The Outlaw isn’t about replacing DJ Snake. It’s another side of me. A space where I can take risks, and deliver an immersive experience that’s focused on sound, visuals, and impact.”

“My job is to be a performer. So you have to perform. You have to be the best, every time. It’s like being a footballer – each game, he has to score a goal.”

As DJ Snake is pushing his sonic limits as The Outlaw, all over the world creatives are concerned about the new limits of artistry, given the slow normalisation of AI. We asked him what he thought the future of electronic music looked like, considering both rapid advances in technology and the subsequent rising value of human input in art. “I think artists will take more risks. Technology gives you tools, but it’s still about having something real to say.”

But is AI being used in the industry right now? “Of course. I love it. You have to adapt. Back in the day, people were against synthesisers. They said ‘Oh, it’s not real’. Then, they were against drum machines, because they were like ‘No, we need a real drummer.’ Then, people were against sampling. They said it wasn’t real music. Once upon a time, they said hip-hop was just a James Brown loop with a guy rapping over the beat.”

He proposes that music isn’t about the tools, but the ideas, and the intentions. His new track “Patience” (ft. Miriam and Amadou) was released with a moving short film featuring Omar Sy, which tells the story of Senegalese migrants. The intention here was to give voice to the voiceless. William grew up amidst a large West African community in Paris, seeing for himself how “when it comes to African migrants, the news talks about the issue, and we talk about them, but we don’t let them talk.”

With this project, DJ Snake set out to humanise the figure of the migrant, not to reference them. “The production of Patience was very personal to me, and after talking to Omar about it, everything came together naturally,” even though it took them a year and a half to even make it to Dakar to film. Patience, indeed.

To William, his work with Omar Sy, Miriam and Amadou is a primary example of the way that intention matters more than anything, more than your instruments. “You’re either gonna make some dope shit, or some bullshit. No matter what you use – AI, whatever – it’s all about the ideas.”

He admits that there are some aspects of the rise of AI that are scary, but he doesn’t want to write it all off too quickly. “Let’s see how it goes, because people used to be mad about the Internet thirty years ago. If you wanna write a letter and go and send it by post, that’s your prerogative – we do emails, baby.”

I think that’s summative of both DJ Snake and The Outlaw, really. Fearless, flexible, and living for the fun of making music, regardless of the market. I suppose, even if I might be a little more concerned about AI than he is, it is exactly that brash confidence that transformed William into DJ Snake back in 2006, and exactly that brash confidence which propels him onwards through his world tour, juggling multiple acts at once.

This year, DJ Snake went global, again, touching parts of the world that he hadn’t previously, and expanding his imprint with a new persona. As we move into 2026, the Year of the Horse, we can expect to see energy, action and progress following transformation, but remember: 2025 was, truly, the Year of the Snake.

Arab Films Are Reaching The Oscars, But The Industry Is Still Lagging

Four Arab films make the Oscars shortlist this year, marking a historic moment for an Arab cinema still struggling for sovereignty.